When it comes to genre fiction —science fiction, fantasy, mysteries, thrillers, horror, romance, related mashups— many authors approach it with a “series mentality.” Rather than conceiving and writing a single book, they think of it as several volumes.

The genre fiction series isn’t a new concept, but its dominance in the landscape is a relatively recent shift in the publishing paradigm, one promoted by the success of one book series after another. But for every successful series, there are far too many that aren’t, which makes it difficult for even an exceptional new series to get noticed. As an added hurdle, while publishers may outwardly seem to be on the hunt for the next big series, they are a difficult sell when you’re a developing author.

What I hope to do with you is look at the various ways I see authors stumble when developing a series, and provide some guidance on how to avoid those pitfalls.

The two types of series

When we speak of a series of books, we tend to mean one of two types: character-driven series and ones with an overarching story.

An overarching story is when each book leads up to a final climatic volume that promises either a big battle or a major revelation, or both. Examples would be Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, George R.R. Martin's A Song of Ice and Fire, and the Newsflesh trilogy by Seanan McGuire.

The overarching story is probably what most people think of when they think of a book series, but it's typically reserved for sci-fi and fantasy. All the books in the series in some way advance the overall story: a new clue found, a henchperson of the “big bad” is defeated, or something like that.

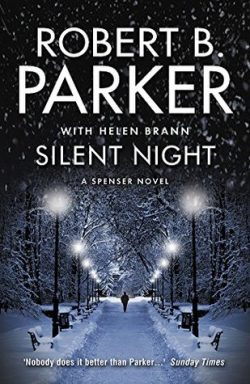

A character-driven series is when each book is a self-contained story featuring a recurring character. Examples are the Spenser books by Robert B. Parker (image right), the Jack Ryan books by Tom Clancy, the Matthew Swift urban fantasy series by Kate Griffin, Conan the Barbarian, and Michael Moorcocks' Elric of Melniboné. These types of series are most typical of mysteries, fantasy, or thrillers.

A character-driven series is when each book is a self-contained story featuring a recurring character. Examples are the Spenser books by Robert B. Parker (image right), the Jack Ryan books by Tom Clancy, the Matthew Swift urban fantasy series by Kate Griffin, Conan the Barbarian, and Michael Moorcocks' Elric of Melniboné. These types of series are most typical of mysteries, fantasy, or thrillers.

Volumes often end with a status quo change for the lead character, such as romantic partners breaking up or a promotion or a serious injury. This type of series is usually easier to continue. The protagonists (or their descendants or related characters) can always find themselves in a new story.

Much like genre mashups, many series are a hybrid of the two, but those tend to skew more toward the overarching story paradigm, as in Harry Potter or Stephen King's Dark Tower books.

While I’m sure you’re already aware of this, writing a series is not something to be taken on lightly. Writing a standalone piece of fiction is hard enough, but with a series, you have a lot more moving parts and each individual book has to advance a bigger story.

Pitfall #1: Thinking of it as "Book One" rather than as its own entity

Very frequently, when I’m asked to edit the first book in a series, the whole thing reads as a very long Act One. Your first book needs to be a compelling read on its own with a complete three-act structure of a beginning, a middle, and an end.

If readers aren’t satisfied with the first book, they won’t care that it is part of a series and no manner of perilous cliffhanger will convince them otherwise. You have to engage them fully at the start with a satisfying, somewhat self-contained story, and then tease them enough that they’re interested to see what’s going to happen next.

Reader engagement doesn’t come artificially from devices like cliffhangers and other “stunts” that rely on information or payoffs that won’t arrive until a later volume. That's not to say that a series can’t use them, only that they can’t be the sole device used to lure the reader into picking up the next volume. The story in the current volume has to feel complete and be compelling first; the cliffhanger or tease is only there to show how the stakes will increase next time.

When writing any book in your series —especially the first one— you need to plot it in such a way that a reader can pick up any volume and get a complete story, not just a chapter in a longer saga. As such, a recap of the current status quo —main characters, their motivations and relationships, and any major pending conflicts— has to be organically integrated into each subsequent volume. Again, Harry Potter is a great example of this.

Character arcs are also critical, as character development needs to be an ongoing process with successes and failures happening in each volume. These then “stack” to form the characters into who they need to be by the end of the series.

As a developing author, selling a book series to a publisher is hard and you can’t count on your series taking off if you self-publish. The better way to approach things is to write Book One with the idea that, if the series doesn’t happen, your readers will still walk away having enjoyed a complete story.

One more thing to remember: when you're looking at acclaimed series, the book with all the awards is almost always the first book, not Book Three or Four.

Pitfall #2: Not having an end in sight.

Yes. You have to have a plan. Just like you should outline each book in the series, so too do you need to outline the entire series, mapping out each advancement in the overall story, both in terms of the series’ ultimate goal, but also how the characters need to develop to contribute to that goal.

If you’re creating an overarching story, there needs to be a definitive endpoint. This isn’t to say that you can’t revisit characters or the world in a later series, but leaving the series open-ended at the outset can lead to meandering. Readers will eventually drift away if there isn’t a payoff for their investment.

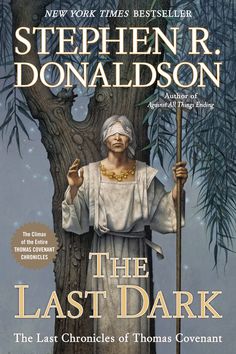

A good example of a “series of series” is the Chronicles of Thomas Covenant, an epic fantasy series by Stephen R. Donaldson. It's a ten-book series that is broken up into two trilogies and then a final quartology (four books). If pressed for a suggestion on how long to make an initial series, I would go with the trilogy. It’s a classic, and it allows the writer to create a three-act structure for the series, and echo that in each volume.

A good example of a “series of series” is the Chronicles of Thomas Covenant, an epic fantasy series by Stephen R. Donaldson. It's a ten-book series that is broken up into two trilogies and then a final quartology (four books). If pressed for a suggestion on how long to make an initial series, I would go with the trilogy. It’s a classic, and it allows the writer to create a three-act structure for the series, and echo that in each volume.

Character-driven series can also benefit from endpoints that give you a clear goal to reach by the end of a certain volume. Endpoints for these series are usually a character-defining moment, such as an end to a long-standing rivalry, a status change at their job, or big life changes like marriage or divorce. The stakes have to start out big and just keep getting bigger. In the Harry Potter series, we know from the outset that Harry has to face Voldemort. But with each successive volume, we are shown how Voldemort’s power grows at an exponential rate and how much Harry has to grow as a character and develop his gifts in order to defeat him.

Many times subsequent novels were sequels instead of a specifically planned series. Some great series didn’t even start out that way, or expanded from something that was originally planned as a shorter run, such as Piers Anthony’s Xanth “trilogy” that now spans over forty books.

So it may help to think of a genre series as more as a book that then spawns a predetermined number of sequels, all of which tell one big story.

Pitfall #3: Not having a plan.

As well as having an endpoint in sight, you need to create a roadmap that leads you there. I mean, if you’re navigationally challenged like I am, the last thing you’re going to do is go on a road trip without a map. It’s the same thing with writing a book series. This, however, doesn’t mean the plan can’t change or mutate along the way.

When making your plan, keep in mind that everything and everyone introduced in the series has to have a purpose, one that relates to both the current volume and to the overall series.

Be careful of the “Miss Marple” syndrome where key characters or pieces of information are introduced so late that they read as a deus ex machina. Make such introductions part of your plan and that they are teased and developed as the series progresses.

Your series plan will outline:

- The major plot of each individual volume,

- The subplots that advance the overall arc,

- The new characters and information that is introduced,

- How elements that are already in play are going to be further teased or developed,

- What will the status quo be by the end of the volume?

- How the stakes are then going to be raised in the next book.

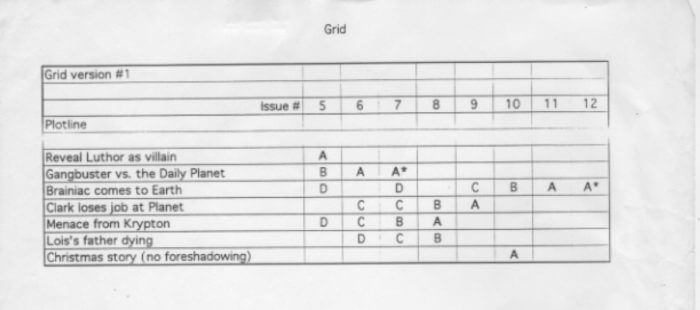

One of the best ways to do this by creating a grid. Not everyone does it this exact way, but it's something I picked up from my time at DC comics. Here's an example of a plotting grid from an old Superman run. It’s not quite the same as what you would use for a series of novels, but it’s a good visual example of what I’m talking about.

The “A” plot is the three-act story that is the focus of that particular volume. Then you can have your “B,” “C,” “D,” and so on plots, which are the elements that relate to the series’ bigger story. As you might guess, the letters have to do with their importance to that particular volume— as well as how much “air time” they get, and how close they are to becoming the “A” plot for a particular book.

So as a simple example, the “B” plot of Book One may become the “A” plot of Book 2, while the “C” plot will bubble to the top in Book Three and so on.

But it doesn’t have to be that simple, and the better-plotted series aren’t. Don’t be afraid to have one plot stay at “D” status for a couple of books before advancing it to “C” or even “B” status. Similarly, you can play with reader’s expectations by having a “B” plot simmer down to a “C” for a volume before starting to advance it again.

Your grid should also outline the developments for each and every essential character and how those changes play into the story for that volume and affect the series as a whole. These developments may also be reflected as one of the volume's “letter” plots.

Again, try to give your primary characters a complete arc that has some sense of closure by the end of the volume, even if it’s a simple as starting in one physical place and ending in another.

Looking again at Harry Potter, note that Ron, Hermione, and the rest often have their own character arcs within the “A” plot and these arcs have an effect on whatever challenge Harry is facing. Another significant benefit of the grid is that it gives you an immediate visual as to whether or not you’re trying to do too much —or maybe not enough— in a particular volume. But most important, it makes it easier to keep track of your various plot threads and assure that none of them become “lost” (where too much time passes before they’re mentioned again) or “stalled” (where it spends too much time at a particular level of importance).

While the first few pitfalls I discussed are pretty major, this last one is a bit more of a minor peril, and may be one that you won’t encounter.

Pitfall #4: Choosing the wrong source inspiration

Happens more with authors who are very into comic books and manga, neither of which are a good model for how to construct a prose series. Not only are they extremely open-ended, but that form of serialization also doesn't translate well to novels.

If you’re looking for inspiration or a model of how to set up your own series, look for similar book series. By the same token, just use these as research on the mechanics of writing a series. In a market that is already flooded with series, the best way for a developing author to be noticed is through originality, not by being the next Harry Potter, Divergent, Twilight, Tom Clancy, or whatever.

If you have any questions about this presentation or about genre series, just drop me a line in the comments box and I'll try to get back to you. If you'd like to work with me on your next project, look me up on Reedsy and let's make it happen.